Dr. Norris Frederick I’ve been traveling down interstates 77 and 81 for about 3 hours, and the roar of trucks going 75 mph is getting to me. I’m on the way to the Virginia mountains…

text and photography by Dr. Norris Frederick “The great point is that the possibilities are really here. The issue is decided nowhere else than here and now. That is what gives the palpitating reality to…

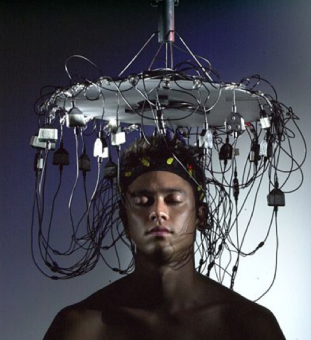

Text and Photos by Dr. Norris Frederick “My experience is what I agree to attend to.” — William James[1] As I awake one morning, I lie in bed thinking about the classes I…

Newport Beach, California By Dr. Norris Frederick Since I wrote my post in early May, “Philosophy for the Pandemic: Stoicism”, the epidemiologists’ warnings about what could happen when stay-at-home restrictions were relaxed have come true:…

“Some things are up to us and some things are not up to us. Our opinions are up to us, and our impulses, desires, aversions–in short, whatever is our own doing. Our bodies are not…

by Dr. Norris Frederick In the video clip [1], George Carlin asks with his inimitable humor, “That’s the whole meaning of life, isn’t it: trying to find a place to put your stuff?” In questioning…

by Dr. Norris Frederick Marie Kondo is quite the thing these days. Her New York Times #1 best seller book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing and her…

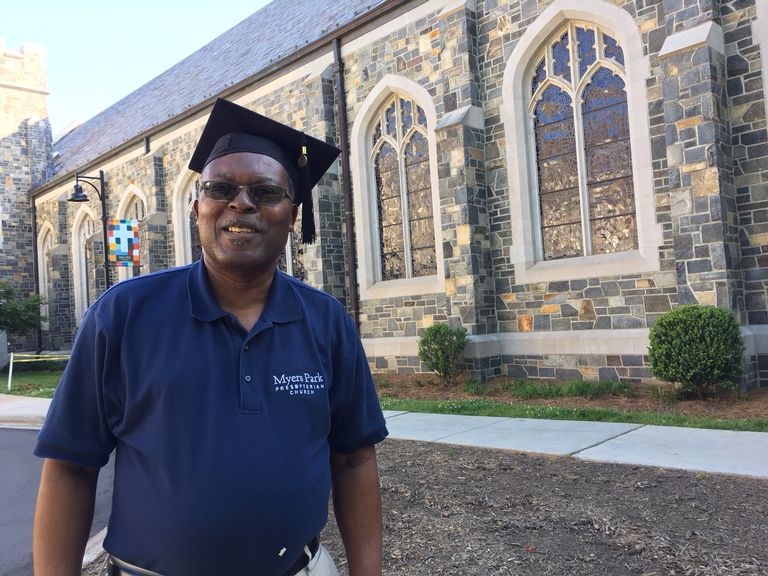

By Dr. Norris Frederick Second in a series After 28 years of attending and watching commencement exercises at Queens University of Charlotte, I’ve come to expect a certain routine of music, speeches, and the awarding…

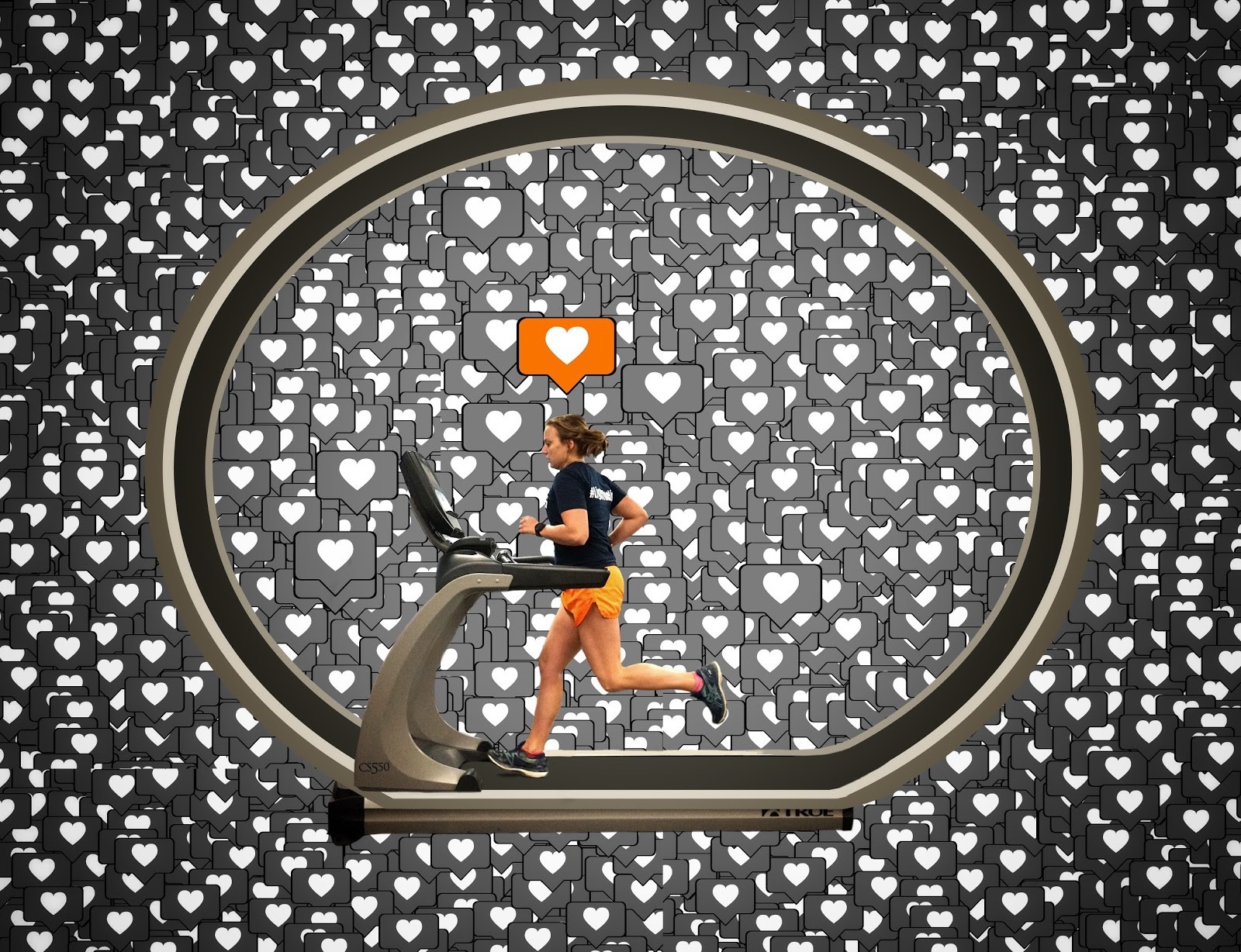

By Dr. Norris Frederick First in a series Thanks to those of you who responded to my most recent post about an assignment from my “Philosophy for Life” course, based on Nozick’s thought-experiment, “The Experience…

By Dr. Norris Frederick This semester I’m teaching my course “Philosophy for Life: What do Great Philosophers and Current Science Have to Say about True Happiness and a Good Life?” [i] The course raises and…