Text and Photos by Dr. Norris Frederick

“My experience is what I agree to attend to.”

— William James[1]

As I awake one morning, I lie in bed thinking about the classes I must teach this day. I need coffee. I stumble out of bed, and as I walk toward the stairs that will lead me down to the coffee-pot, I glance into the bedroom of my 6-year old son Chris. He sees me, sits up in bed, and says, “Dad, is it time to get up?”

“Yes, son, it is,” I reply.

Both his arms shoot up into the air and Chris shouts “HOORAY!”

That happened over 35 years ago. The morning that seemed so familiar and vexing to me seemed to Chris a grand adventure about to begin. Chris tells me that he no longer wakes up that way, and I don’t know that I know any adult who does, but his awakening that morning is worth thinking about. I’d like for us to focus on habit and seeing things anew, with the American philosopher and psychologist William James (1842-1910) as our guide.

Without habits, our experience and lives are shapeless. Without seeing things anew, we miss out on the zest of living.

HABIT

“The great thing…is to make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy….For this we must make automatic and habitual, as early as possible, as many useful actions as we can, and guard against the growing into ways that are likely to be disadvantageous to us, as we should guard against the plague. The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of [habit], the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their own proper work.” [2] – William James

Our habits enable us to accomplish goals well and efficiently, such as walking, or typing this sentence without looking at the keys. Walking, which for most of us is now so routine we rarely think about it, first began as moving by crawling, and then came those first precarious steps, followed by falling down on our bottoms, followed by a few steps to a safe handhold on the nearest chair. Only after many, many attempts and the encouragement of others did we walk steadily, a result of so much practice that our walking became a habit at which we became skilled.

Without habits, dressing ourselves could be a much longer process, and typing would take forever as we would hunt and peck at keys. More complex habits lead us to the deep satisfactions of playing a sport well, or solving problems at home or work. New habits, like wearing a mask during this pandemic, must be developed at first by a conscious effort, and then after enough practice we begin to do it unconsciously.

Contrast our control over habits to this description by William James: “The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion….”[3]

That sounds terrifying to us adults, doesn’t it? We have learned to see a world composed of clear and distinct objects, most which we can name and with whom we’ve developed a habit of interacting. Habits also enable us to develop our character traits, so that we might be said to be reliable, honest, and brave. Or unreliable, dishonest, and cowardly. There is much good that can be said about habits and about developing good habits instead of harmful ones.

And yet…those habits that provide us efficiency and effectiveness can also get us into ruts that mirror those neural pathways formed by habits. Think of the mind as a slope of snow down which you can walk or sled. As habits form those pathways deeper and deeper, it makes it much harder to go down that slope in any other way. And those ruts can lead to dullness and even despair.

SEEING THE WORLD ANEW

If life is nothing but uninterrupted habits our world will be very stale. In between the “blooming, buzzing confusion” world of the baby and the world of endless habits there is an alternative: the art of seeing the world anew. There’s a lot to be said for seeing things anew, as if we were seeing them for the first time. A moment of novelty, consciously maintained, can crack open the shell of habits we have formed.

It’s helpful to remember that, as James points out, what is in our consciousness at any moment is but a fraction of what is present to our senses. Some events, like the photo above of the sunset we saw recently, present themselves overwhelmingly to us, but even then we have to be receptive.

James writes, “Millions of items of the outward order are present to my senses which never properly enter into my experience. Why? Because they have no interest for me. My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind – without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos. Interest alone gives accent and emphasis, light and shade, background and foreground – intelligible perspective, in a word.” [4]

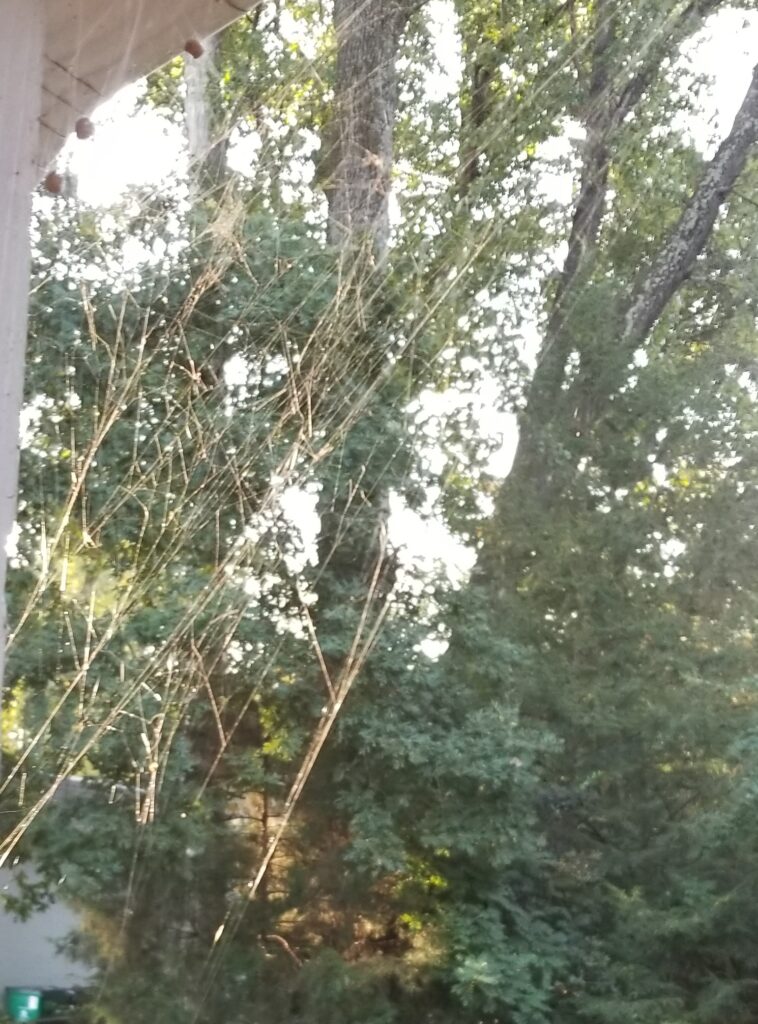

It’s important to form a habit of consciously interrupting all those other habits. Learn to see the world anew. Start with perceptions. Instead of just walking down the steps to get to a destination, breathe in deeply and look around you. Yesterday morning when I stood on the back-porch steps, I saw this:

I am struck by several things about the spider’s web: its beauty; the way the morning sun gleams on it; how it’s a combination of symmetry and irregularity, and when viewed very closely, how strong it is.

The habitual me would not have noticed this spider web, as I might have been mentally planning my morning or — I confess — looking at my phone. If I look for some external validation that my seeing this spider web is important, I become lost in a maze of argument and counter – argument. But if I follow my sense of excitement, I feel a zest for life I would not have sensed in my morning routine.

As James says, “My experience is what I agree to attend to.” I “agreed” to stop on the step and look around me, and then I “agreed” to fix my attention on the spider web. This “agreeing to” involves both what our body and senses are turned to, and also our minds and the habits of mind that we “agree to.”

What are some things you and I can do to develop that sense of seeing the world anew? Here are a few ideas.

- Look for something new in your spouse, friend, adult child, or parent who you have known for many years. We think we know that person so well, but our viewpoint derives not only from the person’s habits but also from our habitual way of seeing them. What do you see anew?

- Do something that’s a bit uncomfortable for you. If you don’t like the cold, walk outside on a cold morning and just stand there for a while. Experience the cold as stimulating, something that makes you alive, something good.

- Do something a bit uncomfortable that connects you to something larger than yourself. Write a letter to the editor or to an elected official. Vote early and in person if your health permits.

- If you read a sacred scripture, see it anew by reading a translation unfamiliar to you. Notice what words and ideas strike you anew.

- Challenge your habit of being busy every moment. Meditate, sitting on the floor or in a chair. Focus on your breath as you breathe deeply, thinking “in-breath, out-breath,” or just “in, out.” Pay attention to what’s in your mind. Calm your mind. Start your day by saying to yourself what the Zen Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us: “I have a whole new 24 hours!”[5] No one had to teach 6-year-old Chris the joy of a whole new day, but we adults need to learn that all over again.

Finally, try this Epicurean exercise. Open yourself to something broader and deeper and infinitely more satisfying than anything you could possibly purchase: the awareness of being, the astonishing fact of being alive when you might not exist at all. Like everything else in the universe, you might never have existed, and you might not tomorrow, but you do now! It’s astonishing to be here, in this place, right now.

Go beyond just thinking about this idea and try it out. Step out into a quiet place on one of these cool fall mornings or nights, and contemplate these words of Lucretius, a Roman follower of Epicurus in the first century B.C.E.:

First of all, the bright, clear color of the sky, and all it holds within it, the stars that wander here and there, and the moon and the radiance of the sun with its brilliant light; all these, if now they had been seen for the first time by the mortals, if, unexpectedly, they were in a moment placed before their eyes, what story could be told more marvelous than these things, or what that the nations would less dare to believe beforehand? Nothing, I believe; so worthy of wonder would this sight have been. Yet think how no one now, wearied with satiety of seeing, deigns to gaze up at the shining quarters of the sky![6]

To share a practice you use to see the world anew,

or to post a comment on my website, click here .

[1] James, The Principles of Psychology (1890), Chapter XI, https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/prin11.htm

[2] James, chapter IV, http://www.yorku.ca/pclassic/James/Principles/prin4.htm

[3] James, chapter XIII, http://www.yorku.ca/pclassic/James/Principles/prin13.htm

[4] James, Chapter XI, http://www.yorku.ca/pclassic/James/Principles/prin11.htm

[5] Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace Is Every Step (New York: Bantam Books, 1991), p. 5.

[6] Lucretius, On The Nature of Things, as quoted in Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, ed. by Arnold Davidson and translated by Michael Chase (Blackwell Publishing 1995), p. 258.

Photo credits: Norris Frederick

I encourage our church folk to engage in a spiritual practice that some call “contemplation,” but I tend toward the term “gazing.” I recall taking a study group to a large and beautiful park in our city – one they had each visited multiple times. I told them that this particular study session would be different. Instead of discussing something, I invited them to find a spot, separated from one another, and then spend 45 minutes in silence just gazing upon the part of God’s creation that was in front of them.

When they came back together after the 45 minutes, I sat back and smiled as they shared what they had seen and felt. More than one reminisced about often doing that kind of thing when they were children and we agreed there is an important lesson in that. Sometimes, new habits and new ways of seeing come more naturally when we allow ourselves to let go of “adulting” for a while, and instead let ourselves be curious, excited children again.

My guess is that your son still gets excited about a new day, maybe once in a while. You might also. Why is that? Maybe it’s the child in you wanting to break free from habits for a while and notice bugs and birds and trees for climbing and creeks for splashing in and…..

As one who affirms that there is a Creator, I marvel at the beauty, majesty, and complexity of what has been created. I try to make it a habit to notice such things, and sometimes I even succeed – much to my good fortune.

Scott, thanks so much for sharing this wonderful description of the spiritual practice of “gazing,” showing again how much beauty and complexity there is to be seen, if we will only gaze. Norris

Norris, this is excellent. Thank you! I fried my eggs in olive oil today, after boiling them for years.

Lynn, thank so much for your kind words. And I got a big smile from your description of how you cooked your eggs!

I will start today in being more present and seeing the world anew. I appreciate the insight this gives me into ways to do that. As I write this I think of what people will say about what I have written. Instead, I want to write it without external validation…doing so is seeing the world anew for me. My contemplative practice has helped me calm my mind, now I want to be more aware when I open my eyes. Sitting in this chair, sipping my morning coffee is a habit that I can build on the see the world anew. Thanks for your words my Brother.

Thank you, brother Ike, for these inspiring words which help me to see the world anew. I really like what you write here: “As I write this I think of what people will say about what I have written. Instead, I want to write it without external validation…doing so is seeing the world anew for me.”

Great post. Reminds me of one day when our son was young, we walked by a bush in front of our house. Suddenly he stopped and said “Look, Mama!” In the bush there were hundreds of baby grasshoppers, the same color as the bush. Good lesson for all of us. The bluebirds on our backyard feeder ever break, for a moment, our daily habits and cause us to be joyful.

How “Rohrish” and Franciscan this practice is! Thanks!

Cynthia, thanks so much for these wonderful moments in which give us the opportunity to be joyful. And what a great sentence you write: How “Rohrish” and Franciscan this practice is!”

Norris, thanks again for another thought-provoking essay. The wonderful example of your six year old’s reaction to a new day reminded me of a Pearl Buck quote “You can judge your age by the amount of pain you feel when you come in contact with a new idea.” I think that quote could be reworded to “You can judge your age by the amount of pain you feel when you come in contact with a new day.” The challenge for anyone who has aged beyond the natural youthful zest for life is to find effective ways to identify new hopes and dreams that will lead to the accomplishment of some worthy act or task that is outside the daily routine. I am always inspired by the accomplishment of the “big wishes” set by some elderly persons such as President George H. Bush’s parachute jump at the age of 90. While that might not be my dream, I recognize how just the act of having that desire and seeing it fulfilled must have added zest to his life.

You suggested great ideas of practices we can all develop that will boost our ability to see the world anew and I will add your suggestions to my list of things I can do to keep focused on that goal.

Thank you, Rebecca! I really like your comments. You made an excellent point for us all to remember: “The challenge for anyone who has aged beyond the natural youthful zest for life is to find effective ways to identify new hopes and dreams that will lead to the accomplishment of some worthy act or task that is outside the daily routine.”

Love, love, love this reminder to be present and make intentional choices. Thank you, Dr. Frederick!

Thanks so much, Teri! I liked your thought about staying in the present and making intentional choices.