“Working on a motorcycle, working well, caring, is to become part of a process, to achieve an inner peace of mind.” — Robert Pirsig

by Norris Frederick

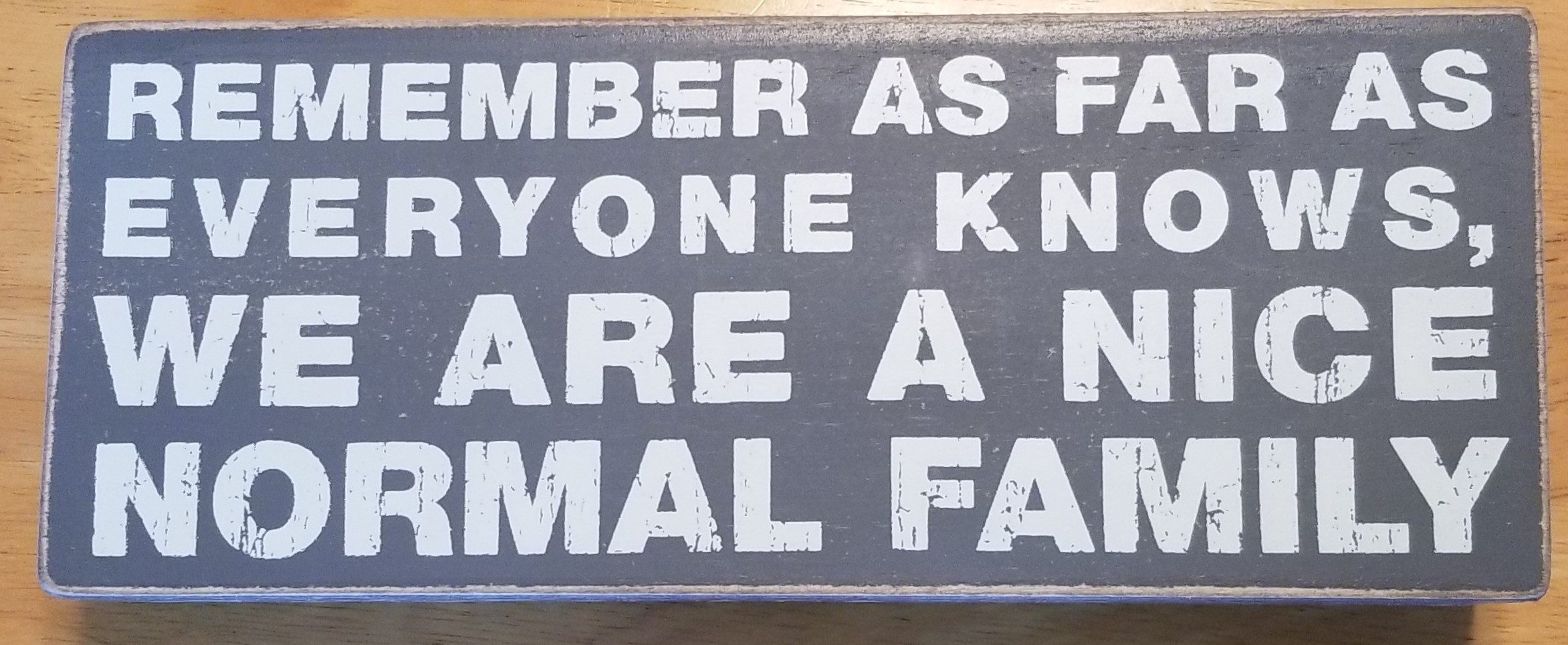

My family preferred to deal with challenges and craziness with humor. Thus the plaque above that my sister Virginia gave to me on a recent birthday, “Just remember: as far as everyone knows, we are a nice, normal family.” I laugh every time I see this sign, as does everyone else. We can all see, in retrospect, the craziness in our families, and if it was not too harmful, we can laugh about it.

My parents, siblings, and I lived in a house originally owned by my mother’s parents. The small house, with three rooms on each side of a central hall that ran the length of the house, was typical of modest homes built in Charlotte around 1915. By the time I was a young teenager, the house was definitely aging. Things needed fixin’. But we had neither money nor the know-how.

TEST12.One evening we heard loud noises coming from the attic, much too loud for a squirrel. As we read and watched television in the living room, we were concerned. What was that? Since we couldn’t figure it out, my brother Charlie and I and our father retreated to the kitchen to get a bowl of ice-milk before Gunsmoke began. We later drifted to sleep, accompanied by the rumbling in the attic.

The next day I was pitching a rubber ball against the front steps when I saw movement on the lower portion of the roof. I saw a large, fat possum ambling toward the side of the roof. It then disappeared. I walked closer to the roof, where I could see a possum-sized hole in the lower left corner of the house, just above the roof. Ah-ha! Mystery solved! I was excited to tell everyone what was causing the noises in the attic.

And what did we do with this knowledge? Well, mostly it enabled us to say with a rueful smile when we heard noises in the attic, “There’s that possum again.” It seems that the six of us living there, including our father, never thought of asking our neighbors to see if anyone had a ladder that would reach up to the roof.

Perhaps the thought that we’d additionally need a board and some nails to make the repair made it out of the question. Our dad would hear the noise, glance up, and then go on reading the paper.

Learning to Think About and Solve Problems

As I became a teenager and later when I had my own family, I began to see ways to live other than ignoring the possum or contemplating the possum. I learned how to fix some things: a flat tire, an electric dryer, an attic fan, loose bricks in a chimney, etc. As long as the result did not require too much precision, I did okay and took great pleasure in solving problems. In fact, I became a bit proud. There are ways to keep the possum out of the attic!

My actions in fixin’ things connected well with ideas. I came to realize there is a conceptual aspect to fixing things, including gaining knowledge about the underlying structure of a thing. In all cases define what the problem actually is rather than just what it first appears to be.

In philosophy grad school, I was delighted to learn that the philosophers known as the American pragmatists – Charles Peirce, William James, and John Dewey – wrote that philosophy itself is an attempt to solve problems. Belief is a satisfied state that is interrupted when doubts arise about the workability of those beliefs.

We believe the roof is in good shape, but then water stains appear on the ceiling. We believe that our race is superior to others, but then we encounter folks of other races who demonstrate the falseness of this belief. Doubts arise.

The doubts lead to an attempt to clarify and then to address the problem. Peirce even wrote an article entitled, “The Fixation of Belief,” about four methods to move from the problematic feeling of doubt to the settled state of belief: tenacity (stubbornly hanging onto whatever beliefs we have); authority (of others, societal leaders who tell us what to believe); pure reason (looking for a consistent set of beliefs); and the scientific method (which goes beyond just consistency to find ways to test various hypotheses about the world).

So now I could not only fix some things, I could think and talk about methods for solving problems! I was feeling pretty good.

The Stubborn-ness of Reality

One Saturday after I’d left grad school, in the year I first began teaching—in a high school, while I finished my Ph.D. dissertation in philosophy — I walked out into our carport and saw that my left rear tire was flat. Ah, a nice easy problem to fix on a pretty fall morning, with plenty of time.

I opened the trunk to pull out the 4-way lug wrench, popped off the hubcap, fitted the wrench to the tire to loosen the lug nuts, and turned it to the left. Hunh! This nut was really tight. But I was young and relatively strong, so no problem.

I bent my knees, gripped the wrench tightly, and turned left with all my strength. What! Instead of the lug nut coming off, the wheel stud broke off from the wheel! How the heck did that happen? It must be some freak incident, perhaps because of a weakness in the bolt. I was agitated, and at the same time a bit pleased with my strength.

Okay, I thought, I’m sure after I remove the lug nuts on the other wheel studs, I’ll still be able to drive the car until I can get it repaired. I moved the wrench to another nut, braced myself, and turned strongly to the left, and broke off another stud. What the hell??!! Now I was furious. This stupid car! I tried another nut, turned with all my might, and—you guessed it — broke off that wheel stud too.

Having spent all my adrenaline, I sat down on the steps and cooled off. I thought finally to look at the car’s manual in the glove compartment, turning to the section on changing a tire. Crap! As I read I remembered: this Dodge Dart is a Chrysler, and Chrysler have left-handed threads on the left side of the car. so to remove the nuts, you turn to the RIGHT, not to the LEFT as on every other car I knew!

Omigosh, how humiliating. I went back to the wheel and looked at the lug studs and saw an “L” clearly stamped at the end of each stud, indicating a left-handed thread. I felt all the energy drain from my body. I finally recovered enough to remove the other lug nuts and drove slowly to the filling station where I sheepishly explained my problem and let the professionals fix the problems I had created.

What caused this minor disaster? Certainly a lack of knowledge of the underlying structure of the bolts. However, the real cause was my pride and then my anger. I threw myself into the torrent of pride and anger, and then found myself swept downstream, ultimately wrecked.

A year or so after “My Humiliation,” I read a book that greatly influenced me, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert Pirsig. The book is both about the most lofty metaphysics and also about…well…fixin’ things. The author goes into great detail about maintaining and repairing motorcyles, as well as the state of mind that achieves quality repairs.

In the 1975 Bantam Books paperback I’ve held together all these years with tape after reading it eight times, the frontispiece quotes two statements from the book:

“The real cycle you’re working on is a cycle called ‘yourself.'”

“Working on a motorcycle, working well, caring, is to become part of a process, to achieve an inner peace of mind.”

That’s it. My ego demanded some magic by which a piece of metal would submit to my strength. Anger became my dominant emotion when it did not, and much to my surprise, that did not end well.

“Clinging Desire”

Reading Pirsig’s Zen led me to be curious about Buddhism. I learned that one of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths is that “clinging desire” or “craving” is the cause of much suffering.

“Clinging desire” results from my belief that there is nothing more important than my individual self. If I can just cling a little tighter to what I want, then I will be satisfied. If I just cling to my righteous anger, then the wheel lugs must come off in the direction I turn them, cling to my desires that my friends and loved ones will change to be exactly as I want them to be, cling to my demands that my cravings be ceaselessly met, then I will be happy.

In fact, since these clinging desires are based on a false view of reality, this attitude results in unmet desires and living in a continuing state of dissatisfaction.

There are some possums we probably should just leave alone. And there are lots of problems we should resolve the best way possible. Either way, rather than demanding of reality that our desires be met, Buddha advises that we get rid of those clinging desires and cravings. If we do, he says, that sense of things being unsatisfactory and unworkable will go away, or at least lessen.

We can train ourselves — through meditation, mindfulness of the present, and practicing compassion — to lessen our desires and paradoxically increase our sense that this life is satisfactory.

Click here to post a comment on my website.

no*************@gm***.com“>To send a comment directly to me, write no*************@gm***.com.

Norris!! What a delight to read your insightful confessional this morning!! Thanks!! Glad you are still thinking, finding humor in this wacko world, and writing!!

Kathy, so glad you enjoyed the post! Thanks for writing. Yes, it’s hard to stop thinking after teaching and getting into the habit, isn’t it? 🙂 I hope you are doing well and finding humor in this wacky world yourself!

Love the stories and the quotes from the motorcycle book.

Thanks, Cynthia!

Norris, I loved this. It will help me so much dealing with a problem I have right now. Thank you, Cousin Barbara

Cousin Barbara, thanks so much for your comments! I’m very happy the post with help you with a problem you’re dealing with right now.

Norris

So many similarities in our memories. Incredible. The only difference with the humor thing and the craziness was that our family really didn’t hide it.

Your observations on fixing things is probably shared by many. I do believe that ones level with patience must be factored in to this…I have had my share of tantrums (as an adult) when “fixing” things, but it was only after retirement that I found a calm that served me well if I had to regroup and try something else.

Having a history of camping also helps as developing a MacGyvering mentality has also been a joy and a Godsend. As for Pirsig and Zen…, one of the demons in my life has always been stripped screws. Hate ’em.

Gary, thank you for your interesting observations. I’m glad you’ve found that calm in fixing things after retirement. And as for the stripped screws, I am with you! I encountered that not a month ago in trying to assemble a nice article of furniture with the cheap screws they sent. Definitely not quality!

Norris, I always enjoy reading your posts but this one was particularly good. It reminded me of failing out of auto mechanics in high school and then attending college and being introduced to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. What a wonderful book. It did not make me a better mechanic but it did inspire me to be a better student. I also had a Dodge Dart with a carburetor that flooded often but I could not repair so I always had a good book in the car as all it really needed was time. Thanks for the broken down drive down memory lane. Keep writing.

John, thanks so much for your encouraging comments and for your witty observations about auto mechanics! A good book in the car sounds like a good solution. 🙂 So glad to know you were positively influence by Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance; me too. Keep on sharing that great sense of humor!

Rebecca, thanks very much for your comments! Every time I’ve thought back over the years about my episode of breaking the studs off the wheel, I experience a rueful smile and laugh. Your comments about “clinging desire” and what actually will work are very helpful and insightful.

Rebecca, thanks very much for your comments! Every time I’ve thought back over the years about my episode with in breaking the studs off the wheel, I experience a rueful smile and laugh. Your comments about “clinging desire” and what actually will work are very helpful and insightful.

I laughed out loud in several places because I can relate.

Any suggestions on how to create in a 13 year old girl the mindset required in that last statement? No amount of meditation or any of the other suggestions are going to eliminate her thought that her life is a disaster if she can’t have all the LuLuLemon clothing that all her friends have

Debbie, Thanks so much for your comment! Glad you got some similar-experiences laughs out of the post. Sadly, you are so right that meditation and even suggestions from “those of us who know” are not going to change the 13-year-old’s mind. I think Aeschylus has it right that for us humans, “Wisdom comes only through suffering.” Frustrating as it is, each person has to learn for herself what previous generations have already learned. 🙂

I never liked those opossums when I saw them in the neighborhood. I thought they were big rats. Maybe I should have had fewer clinging desires…something I will discuss with therapist.

Now that I am older and so much more mature, I am trying to meditate more and get the “life is satisfactory” feeling. Why does it take so long, oh Master? Do you think I am trying to hard, or do I need more facts? More patience? More….

Maybe I need less..

Thanks for making me think.

Ike, yeah, I never was fond of “possums” either! “Grasshopper,” sometimes too little thinking is the problem. Other times, too much thinking is the problem. 🙂

Norris, what a great read…….it really struck a chord with the engineer (problem-solver) in me. And believe it or not I remember our old houses on Jackson Avenue VERY well (though I don’t remember the possum). And I remember our MANY games of throwing the rubber ball against the steps (an exercise I continued for many years). Thanks for the great writing!

Randy, thanks so much for your comments and encouragement! I’m glad you and I share the memories of our old houses and the games with the rubber ball. That possum might have crept in there after your family moved from Jackson Avenue.

Norris, Barbara forwarded this to me and I noticed several similarities. My family was dirt poor, lived in a rental shack, and my Dad, who was not very handy, did not seem to mind that the house was falling apart and none of our stuff worked properly. Our house was surrounded by deep holes that long ago were unproductive gold mines. Neighbors dumped their garbage and who knows what else into these holes so we had rats as big as cats. I think they scared away the possums and raccoons. I’m quite certain that nobody mistook us for a nice normal family.

As for the tire changing problem, my situation was a little different. When I tried to help a lady with a flat tire I also broke off 3 studs but it was not due to left handed studs as was your case. This lady lived somewhere way up north and never washed her car. Years of salt and brine used to melt highway snow caused unbelievable corrosion and rust on her cars’ wheels and undercarriage. Some WD40 helped remove the remaining 2 lug nuts. I put on her spare tire and she also drove slowly to the closest auto repair shop just as you did.

As for Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, I never got around to reading this book but I remember years ago you mentioned it but I can’t remember the context as to how or why I associate your name when I see this title. It doesn’t matter. I plan to read it soon.

Really enjoyed Fixin’ Things

Billy Walker

Billy, thanks so much for writing and sharing the similarities in our experiences. I appreciate your sharing the story about your growing up and your house: hearing about the “rats as big as cats” suddenly made me very grateful for the possum! I’m glad you plan to read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. So glad you enjoyed “Fixin’ Things.”

Norris, you are a great explainer of things! I am so sorry that I never had the opportunity to take one of your classes while I was at Queens working for Patton and Adelaide and Tamara. Thank you for continuing to share your wit and wisdom with the world, along with your goodness and kindness!

Margie, thank you for your comments, which mean much to me! I would have loved to have had you in one of my classes at Queens! I appreciate your taking the time to write here.

Great job, Norris! I enjoyed reading this.

Thank you, Mark!

excellent article and i may contribute a few remarks in a talk i will give tommorow

in which i will quote you.

Thank you for your comment. I hope your talk went well and that the post was useful for you.