Photo by Marek Szturc on Unsplash

by Dr. Norris Frederick

Knowledge is Power

“Knowledge is power.” We’ve heard that many times, and the statement carries a good deal of truth. To know through the scientific method the nature of the coronavirus and its prevention gives us all power over deadly disease, if we will use that knowledge. Neither the knowledge nor the power is absolute, but both are real.

Think of the opposite: the black death of the mid-14th century, when absence of knowledge about the causes of the bubonic plague led to 20 million deaths in Europe, about one-third of the continent’s people. No one knew what caused it. One physician in those days wrote, “instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.”[1] Be alert for those aerial spirits!

So “knowledge is power,” and can be used for good.

“Knowledge is power” can be used for totally selfish purposes, as well. Totalitarian states want to control the flow of information so that only the leaders can have the knowledge of what’s going on, hoping to keep their subjects in the dark. Organizations and individuals can also use knowledge for selfish purposes.

Elected officials claim knowledge even when they don’t have it, to keep their power. Appear confident, speak with authority, and tell the big lie, or lots of little lies, and you may be able to control the polls.

Diametrically opposite to the power of a lying public official is a different type of power: a honest person who says, “I don’t know.” It’s often hard to make that statement. We want to appear confident and knowledgeable, and saying “I don’t know” makes us vulnerable. However, the intellectual humility it expresses is essential to getting closer to knowledge and wisdom.

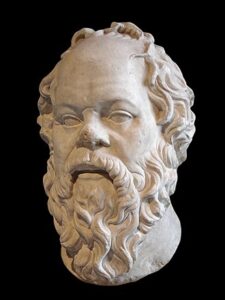

Socrates’ mission and life demonstrate the power of “I don’t know.”

Socrates

Plato’s dialogue the Apology focuses on the trial of his teacher Socrates, in 399 BC in Athens, Greece.[2] Socrates is on trial for “corrupting the young, and not believing in the gods in whom the city believes, but in other new spiritual beings.” At least that is the formal charge, but lurking behind that are background charges, based on Socrates’ reputation. Many Athenian citizens see Socrates as a troublemaker, someone who is leading the Athenian youth away from the tried-and-true beliefs of Athens, teaching them the method of question and answer, based on a logical examination of the answers, to get at the truth. The awareness of “I don’t know” is necessary for engaging in that questioning in the first place; there is no reason to do so if the answers are already known.

One of the background charges against Socrates, he says, is that he seems to possess a certain kind of wisdom. Perhaps he means that many in the jury think that he is arrogant, that he thinks he knows so much, that he thinks he is better than them. To explain this background charge of wisdom, Socrates further angers many of the jurors when he says, “I shall call upon the god at Delphi [Apollo] as witness to the existence and nature of my wisdom if it be such.”

Pretty interesting tactic, isn’t it, when you are accused or worshipping false gods, to call upon the god Apollo as your witness?

The god speaks. What does it mean?

Socrates tells how his friend Chaerephon, who is known as a loyal Athenian, who went on an impulse to Apollo’s shrine at Delphi, where the God’s answers were delivered through the mouth of a priestess. Chaerephon asked the oracle the question of whether anyone is wiser than Socrates, and the priestess replied, “No one is wiser. ”

Socrates is very puzzled by this reply: “Whatever does the god mean? What does his riddle mean? I am very conscious that I am not wise at all; what then does he mean by saying I am the wisest? ”

It is important to understand how the oracle speaks through the priestess. Unlike the God of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, who usually speaks through proclamations, the oracle of Apollo often speaks in riddles.

For example, in the 6th century BCE, Croesus, the king of Lydia, was trying to decide whether to wage war against the Persians so he asks the oracle, “What will happen if I go to war? “

The oracle replied, “If you go to war, a mighty kingdom will fall.”

The king was delighted and quickly waged war. And lost. He did not understand what the oracle meant: a mighty kingdom did fall, but it was his own!

So Socrates figures he must try to understand the god’s pronouncements. Even though he is convinced that he is not wise, he does not just toss aside the god’s statement, for “Surely the god does not lie.”

Socrates does not use the god’s statement for his own power. He does not do what many a huckster in our era might do: claim that he has been anointed by the divine and given a special power, set up a cable “ministry” where devout followers can praise him and send him money, and receive in turn earthly blessings, perhaps a Lamborghini, in exactly the right color.

Instead, Socrates decides to investigate, to think critically through this puzzle. He decides to go to those who have a reputation for wisdom. If he finds just one wise man, he will be able to refute the oracle and say to the god, “This man is wiser than I,” even though the god said no one was wiser.

He first examines one of the city’s politicians. ” My experience was something like this: I thought this man seemed wise to many people, and especially to himself, but he wasn’t. Then I tried to show him that he thought himself wise but wasn’t.” You can only imagine how unpopular this made Socrates with the politician.

Does Socrates’ experience, by any chance, remind you of some politician you might know? Someone who has a huge ego, who manages to convince people that he has the answers, that he knows, and all they must do is elect him, and they will live in live in a land of milk and honey? But of course, once in office his supposed knowledge doesn’t actually solve all the problems, for he doesn’t really have knowledge. Instead, he has the skills and tricks of persuasive speech, whipping up a crowd.

Socrates concludes after he examines the politician. “… he thinks he knows something he doesn’t know, whereas I, since I don’t in fact know, don’t think that I do either. At any rate, it seems I’m wiser than he in just this one small way: that what I don’t know I don’t think I know.”

There is a powerful wisdom in knowing what we don’t know.

Then Socrates questions the poets and finally the craftsmen, who in our day might be better seen as the businessmen. The businessman obtains success in a certain area, perhaps producing a certain product or maybe a chain of hotels, and because of success in this one area believes he is extremely knowledgeable, an authority on everything. Have you ever had that experience with a businessman, a know-it-all with lots of self-pride, who clearly does not know it all?

And it’s not only businessmen who have this problem. Plenty of professors who know their subject well think they are authorities on everything. This definitely includes some philosophy professors.

Socrates’ conclusion from all his investigations is that “It’s pretty certain that it is the god who is really wise, and by his oracle he meant that human wisdom is worth a little or nothing. And it seems that when he refers to the Socrates in front of you and uses my name, he makes me an example, as if he were to say, “That one among you is wisest, mortals, who, like Socrates, has recognized that he’s truly worthless as far as wisdom is concerned. “

If you read very carefully what the oracle said, it was “No one is wiser [than Socrates].” It would be easy for us, and for Socrates, to jump to the conclusion that he is the wisest person, above all others. Instead, “no one is wiser” leaves room for the fact the others are equally wise to Socrates, and now at the conclusion of the investigations we see how others, including ourselves, may be wise.

Socrates is wise in realizing he is not wise, and we can be wise in the same way.

Is That All I Need?

Is it enough to realize you don’t know, you’re not wise? If you’re a college philosophy student who’s just studied the Apology, can you go home and tell your parents what their hard-earned money has achieved: you, their child, knows that you do not know, you have become wise in realizing he/she is not wise? Will those parents fall at your feet in worship of you?

Well, no. Intellectual humility, realizing that we do not know, is essential in initiating a search for truth, but it’s not sufficient. In addition to intellectual humility, we need intellectual curiosity, a desire to know.

Aristotle, Plato’s student, begins his Metaphysics with the statement, “All people desire to know.” I think he’s right about that. Of course, many things throw cold water on that fire of desiring to know: authority, peer pressure, media, social media, complacency, discouragement, and teachers who are more interested in being in control than in promoting a spirit of inquiry, to name a few.

We also need training and practice in developing skills of inquiry, whether through the scientific method or learning the basics of questioning, of logic. With these strengthened abilities, we can develop intellectual confidence.

We need to live a life that balances intellectual humility and intellectual confidence, and to have the courage to live between these two states. Let’s start with an awareness of what we don’t know, work to increase our knowledge, and remain aware of the limitations of human knowledge.

_____________________________________________

[1] https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death

[2] Plato, The Apology of Socrates, in The Trials of Socrates, edited and translated by C.D.C. Reeve (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2002).

To live between intellectual humility and intellectual confidence with balance requires intellectual curiosity which means having the courage to ask questions when it is discouraged to do so for it can be destabilizing and threatening to many — especially to those in power. I think of those like Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and many others known and unknown who were courageous … Thank you. I find the categories of intellectual humility, intellectual curiosity, and intellectual confidence most helpful and having the courage to live between….

Gary, thanks so much. Your insights about courage, and your examples, are a very helpful addition to this discussion.

This opens my eyes. Am I wise because I know I am not wise? Because I never questioned that, but who is wise if all deny they are wise. I guess those who are wise explain why we are on this Earth. In that way, Professor Norris is wise.

I am still wrestling with those who accept surface knowledge as truth, or wisdom. It seems that they will accept that they are not wise, but do not take the step to acquire wisdom, just accept what comes in as truth from their tribe and let it ride.

Ike, thanks so much for your comment. Your final paragraph really has me thinking, about folks who don’t even seek wisdom (and this is true for all of us in some aspects of our lives), reminds me of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.”.

Thanks for a thoughtful and deft examination of our psychological , social and political state,Norris.

“More will be revealed.” 🙂

Thanks so much for your comment, Scott. And yes, to be sure, “More will be revealed”! 🙂

Thanks Norris. “Anyone who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities” – Voltaire. My favorite thought since last January

Olga, thanks for your comment, and the wonderful quotation!

As I completed my doctoral work, I was reminded of what, at least for me, is a truth of life: the more you learn, the more you realize that you don’t know.

As a pastor, I am very comfortable with the need to say “I don’t know.” Sometimes the question prompting that answer has to do with the nature of God. God is God and I’m not, and there are things about God I will never understand. “I don’t know” may be the correct answer, but it shouldn’t end there. I need to also offer to come alongside the person and work with them as they seek answers (wisdom?).

Often, the question has to do with something related to pain and suffering, and wondering why a loving God would allow such a thing to happen. Bumper sticker answers don’t work, and neither does a response along the lines of “Well, God’s ways are not our ways and we should never question.” Plenty of people in Scripture had questions for God, including Jesus (see Matthew 27:46). God can handle our questions. Sometimes we find answers and sometimes we don’t, and that’s okay. Even when we don’t arrive at a definitive answer, we’ve probably gained some knowledge and maybe even some – dare I say it – wisdom. And that makes the search for an answer worth the time and effort.

Scott,

Thanks so much for your fine insights in your comment on my post. It’s a great thing, I think, for people to have the example of a pastor saying. “I don’t know.” Of course, the conversation doesn’t stop there, as you point out.

I love your final sentences, and so would Socrates: “Sometimes we find answers and sometimes we don’t, and that’s okay. Even when we don’t arrive at a definitive answer, we’ve probably gained some knowledge and maybe even some – dare I say it – wisdom. And that makes the search for an answer worth the time and effort.”

I had to read this several times before commenting. Without acknowledging what one does not know, I don’t think that a person can be open to learning anything new.Thus, a person cannot be wise or grow in wisdom without starting from not knowing (over and over again.)

Cynthia, thanks so much for your helpful comment.

Yes. Currently in the US so many people are screaming they know truth and don’t need to listen or discuss or learn, using “knowledge” to bully. This trend is based in fear and insecurity.

Andra, thanks so much for your insightful comment. I think you’re right about so much of the screaming coming from fear and insecurity. It’s good for all of us, including me, to keep that in mind both about others and ourselves.

Thank you once again Dr Norris for reminders on how life wisdom comes incrementally, to some, and is not necessarily for us to perceive about ourselves. And to learn that riddle revelations often are mis-interpreted by receivers.

Charles, thank you — as always — for your insightful comments. “Riddle revelations” is such a great phrase; thanks for that.

Norris, I believe there is power (or at least the power of truth) in knowing that “I don’t know”. But as you say this “power” is useless if we do not TRY to know. In my career I maintained the motto “Search for truth”…..and this served me well as my colleagues and I tried to get to the source of a problem, or to a true “bottom line” answer. Also I agree with your implied premise that those in power who do NOT admit ever that they “do not know” are extremely dangerous, as has been demonstrated in DC.

Randy, thank you for your fine insights. I know that you did follow the motto “search for truth” in your career, and we are all the better off for that. Both goodness and evil can radiate out from out actions, as you point out.