By Dr. Norris Frederick

Third and final in a series on death

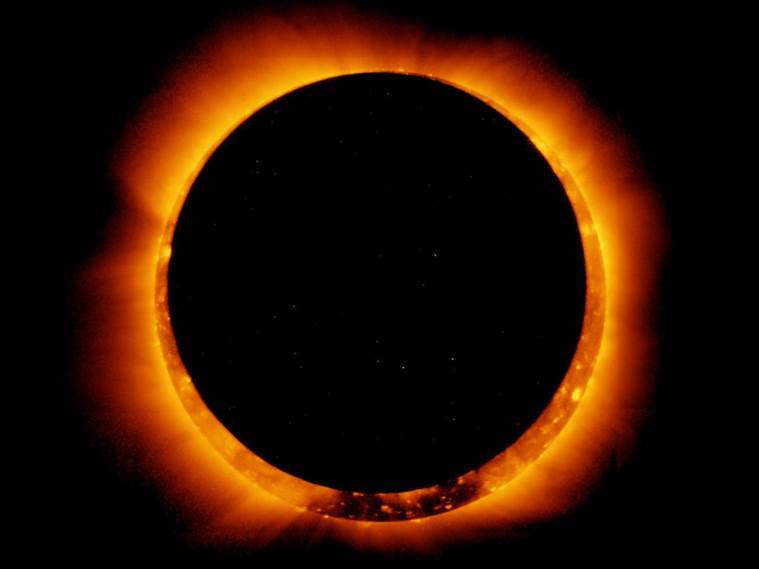

The recent solar eclipse was almost total here in Charlotte, and a large number of people gathered on the Queens University campus to watch the event. For the folks around me and those shown in videos from around the country, the atmosphere was of celebration or deep awe at this rare celestial event. At our campus there were enough eclipse sun-glasses to share so that everyone could gaze as the moon came closer and closer to blocking the sun. For weeks, there had been dire warnings about the dangers of looking directly at the sun. I wonder: should there be similar warnings about staring at death, as it eclipses our lives? Is our joy destroyed by that evil shadow creeping over our vitality?

We always need lenses through which to look at the deepest philosophical questions, and I find the philosopher and psychologist William James to be of great help. In The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902), his method is to collect and categorize human responses to the question of “What is the character of this universe in which we live?”[1] After examining these responses as shown in “feelings, acts and experiences,”[2] he offers philosophical hypotheses and conclusions to answer two key philosophical questions, what is true and what is best.

The healthy-minded temperament and strategy

James describes two main types of temperament toward viewing evil and death. The first he calls the “healthy-minded”: “In many persons, happiness is congenital….when unhappiness is offered to them” they “positively refuse to feel it [unhappiness], as if it were something mean and wrong.”[3] Evil has no reality. Their soul is “sky-blue” and their “affinities are rather with flowers and birds…than with dark human passions… [and they] can think no ill of man or God.”[4]

People with the totally healthy-minded temperament manage not to see the reality of death at all. When James published The Varieties in 1902, there was in America (as there is now) a great emphasis on happiness or “healthy-mindedness.” Today those who are not naturally as optimistic can voluntarily adopt strategies to become happier through therapy, medication, or meditation. Healthy-mindedness can be not only a temperament, but a strategy.

In my most recent post on death, “Out of Sight, or Front and Center?” I wrote of our study tour visiting the Capuchin Crypt in Rome, where the bones of thousands of past monks are on display. The healthy-minded in our group would have preferred to never have entered in the first place (“Why go to such a gloomy place on such a beautiful day, and in romantic Italy, for God’s sake!?”). And many of us left after viewing the Crypt moving as quickly as possible to find a cappuccino or a beer, trying to restore healthy-mindedness, happiness. And why not? Don’t we want to be happy? Isn’t happiness a good thing? And if the young naturally cannot conceive of the reality of their death, why should we focus on it, either?

The temperament of the sick soul

James describes a second temperament which he names the “sick soul.” For people with this temperament “the evil aspects of our life are of the very essence…the world’s meaning most comes to us when we lay them most to heart”[5] For these people, it’s as if they are born to a life where from every pleasure, “something bitter rises up:…a touch of nausea…a whiff of melancholy,” which have “a feeling of coming from a deeper region.” [6]

If you’ve ever had a time when evil and sadness overwhelmed you for extended periods of time, you know how inadequate this description is to what you felt or feel. We know now that at least part of this temperament (as well as the temperament of the healthy-minded) is genetic. Whether from genetic or other reasons, the sick soul can overcome us. In The Varieties, James gives a vivid description of someone overwhelmed by depression.

Whilst in this state of philosophic pessimism and general depression of spirits about my prospects, I went one evening into a dressing-room in the twilight to procure some article that was there; when suddenly there fell upon me without any warning, just as if it came out of the darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence. Simultaneously there arose in my mind the image of an epileptic patient whom I had seen in the asylum, a black-haired youth with greenish skin, entirely idiotic, who used to sit all day on one of the benches, or rather shelves against the wall, with his knees drawn up against his chin….This image and my fear entered into a species of combination with each other. That shape am I, I felt, potentially. Nothing that I possess can defend me against that fate, if the hour for it should strike for me as it struck for him. There was such a horror of him… that it was as if something hitherto solid within my breast gave way entirely, and I became a mass of quivering fear. After this the universe was changed for me altogether. I awoke morning after morning with a horrible dread at the pit of my stomach, and with a sense of the insecurity of life that I never knew before, and that I have never felt since. It was like a revelation; and although the immediate feelings passed away, the experience has made me sympathetic with the morbid feelings of others ever since. It gradually faded, but for months I was unable to go out into the dark alone.[7]

James later admitted the sufferer was himself, in a period of depression early on his life. Clearly, the category of the unhealthy-minded was no mere philosophical abstraction for James; he had experienced it with the depth of his being.

What strikes many people immediately upon viewing the Capuchin crypt and all those human bones is a feeling of disgust, easily seen in the faces of the viewers. The word several people in our group used is that it’s just “morbid.” If that viewing and that sense of morbidity, darkness and gloom dominated a person for long periods of time, we might well judge that to be unhealthy. To the sick soul it is not the pleasure of the beer and human company that is the most real, it is the feeling of death to come.

Which is true and best: the healthy-minded or the sick soul?

Like so many questions of this sort, the question of whether the healthy-minded or the sick soul presents a true view of reality and is the best way to live is a false dilemma. There are other possible answers. There are both different levels and combinations of these two temperaments that form a philosophy for living.

There is something to be said from within the morbid-minded view, especially when it is taken not from the extreme of debilitating depression but from its more philosophical form. James writes that the view of the sick soul is “based on the persuasion that the evil aspects of our life are of its very essence, and that the world’s meaning most comes home to us when we lay them most to heart.”[8]

I think that is why so many of the great works of literature deal with death and suffering. That why Tolstoy grabs us so strongly with the opening sentence of Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” It’s the truth and reality of the unhappiness that reels us in. It’s why Walker Percy’s The Second Coming has stuck so many as a powerful truth, as the central character deals with the sadness and emptiness he feels and sees in his past, his self, and the society around him.

James points out that there are different levels of both healthy-mindedness and morbid-mindedness people have some mixture of the two temperaments. He stated in his 1895-96 lectures on abnormal psychology that “A life healthy on the whole must have some morbid elements.”[9] Finally, he argues that the morbid-minded philosophical position is superior in some ways to the healthy-minded, as the former ranges over a “wider scale of experience” and because “the evil facts which [healthy-mindedness] refuses positively to account for are a genuine portion of reality.”[10]

Refusing to see and experience the reality of death and suffering narrows and constricts our experiences, while acknowledging and feeling their reality paradoxically enriches our lives. Acknowledging and feeling the reality of death, suffering, and evil turns out to be healthier than trying to deny it.

A truly healthy philosophy for living has the proper relationship between the healthy-minded and the sick soul. An Epicurean life of simple pleasures and serenity is not enough, for an adequate philosophy will value the struggle.

A healthy worldview calls both for acknowledging and for an overcoming of death in some way, whether by a life demonstrating courage and human excellence, and/or by a life continued – in some way — beyond this one, through an afterlife, reincarnation, or the influences we leave in the world. We are elevated by the lives of good, honest, courageous, and hopeful people, and they inspire us to do likewise.

__________________________________________________

[1] James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, (Penguin Classics, 1982), 35.

[2] James, The Varieties, 31.

[3] James, The Varieties, 75.

[4] James, The Varieties, 8o.

[5] James, The Varieties, 131.

[6] James, The Varieties, 136.

[7] James, The Varieties, 160 – 161.

[8] James, The Varieties. 131.

[9] James, “Notes for the Lowell Institute Lectures on Exceptional Mental States,” Manuscript Lectures, (Harvard University Press), 63.

[10] James, The Varieties, 163.

Photo Credit: NASA

You’ve done it again, Dr. Frederick. This post speaks to the ongoing questions and orientations to life that too often seem “given” to us rather than as types of orientations. I really appreciate seeing these approaches as strategies. Thank you for translating James’ work into helping me meaningfully navigate the chaos and unpredictability of my responses to events. This is what I will take with me today and throughout the week.

“A truly healthy philosophy for living has the proper relationship between the healthy-minded and the sick soul.” Thank you!

Zachary, thanks so much for your comments. I especially liked, “This post speaks to the ongoing questions and orientations to life that too often seem “given” to us rather than as types of orientations. I really appreciate seeing these approaches as strategies.”

These words are comforting to me as I enter the final quarter of my life (I hope). How do we accept the death that is sure to come without acknowledging the pain, suffering and loss that we will experience. James and Frederick enlighten me to the fact that we can acknowledge both the fear and the joy of life while still living in reality. I will try harder. Thankfully, there is light after the darkness that we will inevitably experience.

Ike, thanks so much for your thoughtful comments. I especially liked, ” James and Frederick enlighten me to the fact that we can acknowledge both the fear and the joy of life while still living in reality.”

An interesting article, Norris. What I fear in our culture today is the need for everyone to be “happy,” which I think fails us in so many ways. Rather I believe we need our lives to be meaningful and that includes acknowledging aging and death. My preacher husband has always said that being with someone at the moment of death is a powerfully moving experience and incredibly life-affirming. A few years ago, I had a personal epiphany that the last great adventure of my life will be my death and what lies beyond (of which I’m not truly certain). Since then I haven’t worried too much about my own death. But certainly the death of those I love would still be emotionally traumatic for me.

Miriam, thanks so much for your l comments. I especially agree with your point that instead of happiness, “,,,I believe we need our lives to be meaningful and that includes acknowledging aging and death”

Thank you for these insights Norris. In the last few years I have often grappled with these questions. Your thought that acknowledging and feeling the reality of death “paradoxically enriches our lives” rings very true for me, too.

Barry, thanks so much for sharing your insights. I especially like, “Your thought that acknowledging and feeling the reality of death “paradoxically enriches our lives” rings very true for me, too.”

Having comfort in the darkness means dwelling in it from time to time, perhaps even voluntarily. As we often use the light/dark metaphor in constructing meaning in the world, it is often to shun the dark. But as I often tell my students when we consider nihilism as valid, having voluntarily entertained this proposition is invaluable for the times when life pulls out the rug and makes all light, meaning, and beauty seem insubstantial.

P.S. love the lessons on James. Good stuff.