by Dr. Norris Frederick

In the video clip [1], George Carlin asks with his inimitable humor, “That’s the whole meaning of life, isn’t it: trying to find a place to put your stuff?” In questioning “stuff” he’s making a very similar point to the question Epicurus asked in my most recent post about Marie Kondo’s book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, “why did you buy all this crap in the first place?”

I wrote last time about Kondo’s methods, my own desk piled with papers and stuff, why Epicurus thinks Kondo does not go far enough, and the ideal of simplicity. Some of you wrote me that Kondo’s method and the feeling of control brought by keeping only what brings you joy really works. Some wrote wittily that your own working conditions are quite different from Kondo’s ideal. One friend wrote, “My desk is about like yours, and I like it that way-it is comforting and makes me feel attached to life; however, I do declutter now and then.” Another wrote, “I have a dual approach to my cluttering/hoarding/neurotic stacks, piles, and general messes: avoidance and denial, which has long served me well; and motion—every time I move a pile it gets smaller, motion = attrition.” A third wrote, “I am inclined to delete this challenging email, so I don’t have to think about the stacks of stuff in my office until they start toppling over.”

Several of you shared in different ways this later-life sentiment: “Being executor of my brother’s estate and having to deal with his entire lifetime of voluminous and useless clutter has at least made me think: I DO NOT want to leave tons of useless stuff for my kids to have to deal with when I am gone.” And another friend said, “When I travel abroad, and especially to places like rural India and rural Jamaica, my sense of how much ‘stuff’ is really necessary gets – well – turned upside down. Basic needs must be met, of course, but we Americans live in what is arguably the most materialistic culture on the planet and we are products of our culture, whether we like it or not.”

These last two comments bring us back to “useless stuff.” Epicurus asks us a question that goes far beyond Kondo’s book:

“Why do you buy all this crap in the first place? Why have you bought an enormous home and then tried to fill every part of it with expensive items? Aren’t you constantly worried about paying the mortgage and buying even more expensive stuff that you see on the strange screen where you stare at this enormous marketplace?

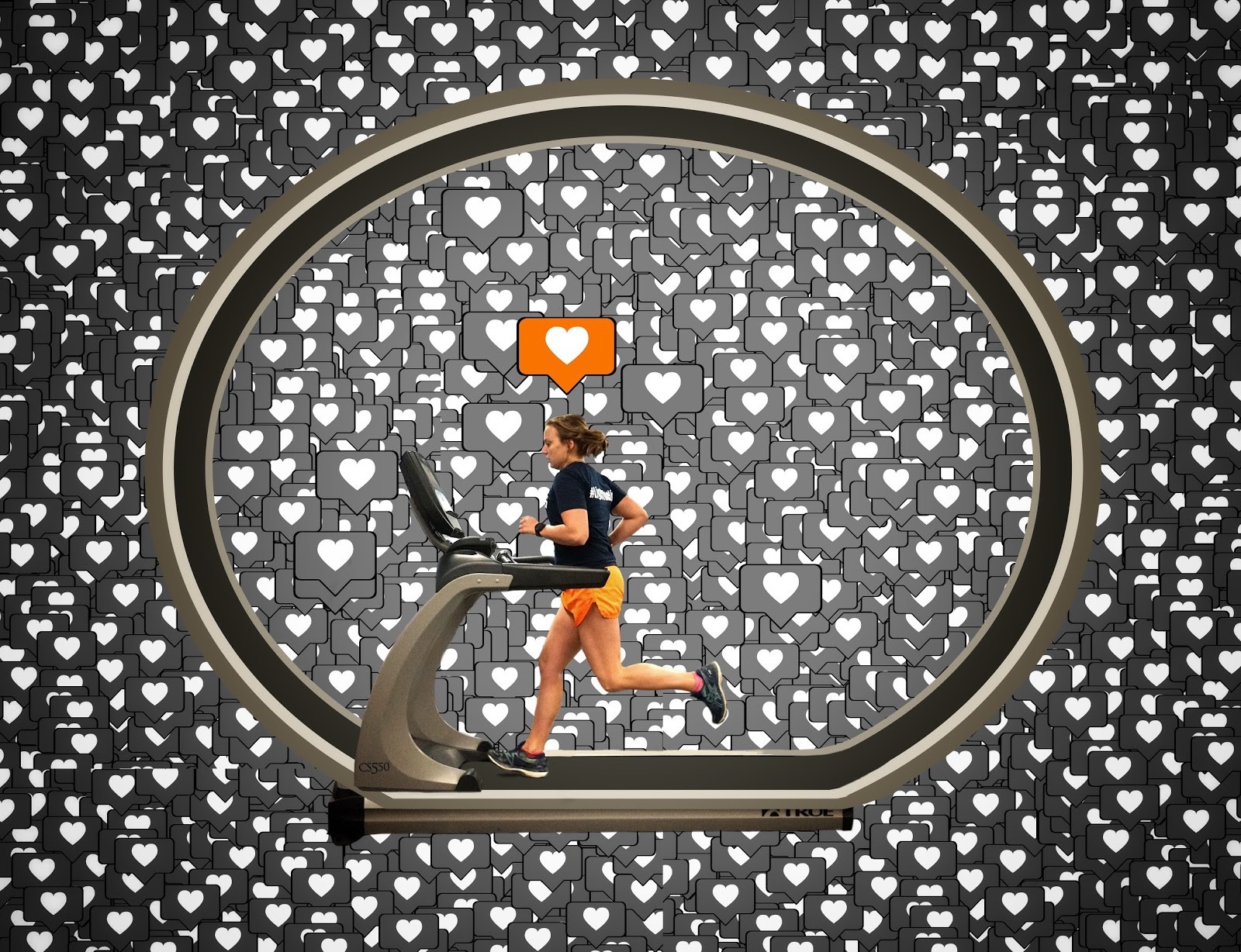

The Hedonic Treadmill

(photo/graphic above by Ida Osterman,

Queens University of Charlotte, used by permission)

One pervasive force in accumulating stuff is what psychologists call the “hedonic treadmill”[2] (“hedone” is Greek for “pleasure”) : the belief that gaining that new car or new shirt or a 5% raise that I see in front of me on the treadmill will finally bring me happiness. However, as Jonathan Haidt writes, “Nerve cells respond vigorously to new stimuli, but gradually they ‘habituate,’ firing less to stimuli that they have become used to.”[3] Instead, over time and due to hedonic adaptation, that object attained loses its initial excitement and hope, and is replaced in our view by another object or later a bigger raise which we think will bring us happiness. And our striving and stress on the treadmill goes on and on and on.

So perhaps we should do as Epicurus argues and focus only on the simple pleasures which have almost no negative consequences: eating simple food and drinking inexpensive wine; reading; philosophical conversation; and friendship. In fact, however, the ideal relationship between material goods and the good life is complicated. After all, even with all his emphasis on focusing in simple pleasures, the life of Epicurus and his followers required money to acquire the school he opened in the garden (“The Garden”) of his house.[4]

American History and The Ideal of Simplicity

A study of American history also demonstrates a frequent avowed love of simplicity but also the difficulties in living that life, as David Shi masterfully illustrated in his book The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture .[5] The proper balance between achieving the necessities of life and following the higher calling of man, hoped the Puritan Governor John Winthrop, could make America a “shining city on a hill.” To help people achieve the good life, the Puritans enacted laws that prohibited the wearing of any vain accumulations of stuff: gold buttons or silk scarves allowed.

So whereas the Epicureans invited followers to join them in choosing and living a simple life, the Puritans decided to cut out that cumbersome individual decision process and force citizens to live such a life.

The founding fathers of this country were strongly attracted to the histories of the late Roman republic which “portrayed the Republic as a serene, pastoral nation of virtuous citizens.” For a number of years, Thomas Jefferson hoped that the United States could be an industrial yet decentralized nation, and thus could maintain agrarian values. Jefferson declared himself an Epicurean, stating in a letter that “to be accustomed to simple and plain living is conducive to health and makes a man ready for the necessary task of life.”[6]

Of course Jefferson didn’t lead a particularly modest life, as knowledge of his slave plantation and a visit to Monticello make clear. But Jefferson stated an ideal that remained strong in America.

The individualistic spiritualism of the Transcendentalists in the mid‑19th century led to fascinating attempts to live out the simple life. Emerson restates the idea of the Epicureans and Stoics when he writes, how “to spend a day nobly is the problem to be solved.”[7] But Emerson’s home required domestic servants, which friend Thoreau criticized severely. Thoreau went to Walden Pond (on land Emerson owned) to learn the necessities of life, and to write. His two‑year stay there relieved him of many illusions. The Indians and the farmers he met in his travels were not the noble children of nature his romanticism had pictured. He once was excited by meeting a Canadian woodsman who told Thoreau that if “it were not for books,” he “would not know what to do [on] rainy days.” Imagine Thoreau’s disappointment when he discovered that the man’s only books were “an almanac and an arithmetic” and that he knew nothing and cared less about spiritual views or current social issues such as the antislavery movement.[8]

Thoreau decided that wilderness and the primitive life were necessary but not sufficient for the simple life, a view that became increasingly popular around the turn of the century and remains so today in somewhat different form, as we Americans climb into our “recreational vehicles” or take luxury cruises and either way take our computers with us on our return to nature, where often the first thing we do is to check the phone reception to see if it’s adequate for receiving internet.

What’s the Answer?

President Jimmy Carter addressed the growing consumerism of America in his famous “malaise” speech of July 18, 1979, saying, “owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We have learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or meaning.”[9]

Epicurus pursues that meaning by focusing on some simple pleasures. Instead of just carefully going through your stuff and getting rid of it, quit organizing your life around material possessions that ultimately distract you from a life spent on more important things, like friendship, reflection, memories that matter and the joy of being alive.

The Reverend Scott Killgore, once my student, now teaches me as he insightfully puts it all into perspective:

“I would argue that our cultural addiction to material possessions is a spiritual issue. Unless that spiritual struggle is acknowledged and dealt with, then we will find ourselves to be like addicts who struggle to break free, but repeatedly fall back into the clutches of whatever destructive addiction has taken hold of their lives. Simplifying our lives in terms of material possessions is commendable, desirable, and something that would benefit most anyone. But, it may be more difficult to simplify our understanding of what makes us genuinely happy.

“Simplifying our lives when it comes to material possessions is a good way to start, but it marks the beginning of a journey, not one’s arrival at a desired destination.”

To post a comment on my website, click here

and then scroll down to “Leave a reply.”

Top photo credit: Ida Osterman, Queens University of Charlotte, used by permission

[1] From YouTube, search “George Carlin Stuff.” Thanks to two friends who suggested this video.

[2] Jonathan Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 86. Haidt attributes the concept of hedonic adaptation to Brickman and Campbell’s article, “Hedonic relativism and planning the good society” (1971).

[3] Haidt, 86.

[4] John Cooper, Pursuit of Wisdom (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012),145.

[5] David Shi, The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture (Oxford University Press, 1985).

[6] Shi, 77.

[7] Shi, 130.

[8] Shi, 147.

[9] Shi, 271.

Great writing this month, Norris. Can’t wait until next month to see what you come up with. I have less “stuff” now than at anytime since I left my parents. Since I live in Joe’s Condo, I cannot fill it with more “stuff”. If I need something important like a new coffee maker or a new electric toothbrush. I study and think hard about what to buy. So my simplifying journey has begun – who knows where it will lead.

Ike, I really like your story about having less “stuff” and about how you have simplified your life. Your journey is a good one, and I am learning from you and our discussions about how much we actually need. I’m glad you liked my post.

Thank you Norris for an intellectual investigation of who we (think) we are by helping us better see our relationships with our “things.” This is, simply put, the best of philosophy of living. Thank you for helping me and us understand the history of our material relationships and the complications that continue to confound us. It’s as if learning to manage this tension is a rite of passage in American life (e.g., learning to constantly say no to an industrial complex that profits from us saying yes–over and over again–to things that promise).

And thank you, Zachary, for your insightful comments. I’m glad you found worth in the post. Your thought in your last sentence speaks so well about the hedonic treadmill of our lives in the U.S.: “It’s as if learning to manage this tension is a rite of passage in American life (e.g., learning to constantly say no to an industrial complex that profits from us saying yes–over and over again–to things that promise).”

Norris,

Great post! I enjoy the way you weave philosophical thinking into our modern dilemna of “too much stuff.” I think Reverend Killgore is correct about the deeper issues involved. In order to live a meaningful life, we must turn inward to face ourselves and ask the hard questions: Am I living a life true to myself? Does my life have meaning and purpose? Have I left the world a better place? How much more soothing to turn our focus to managing our “stuff.”

Nancy, thanks so much for your insightful comments and calling attention to the big questions which we need to be answering, not only with our thoughts but with our lives.

The important fact–an economic one in fact– around this consumer materialism is that the US economy thrives when its inhabitants buy stuff. This is what we have become generally since the end of WWII. The now pervasive global economy is no longer of the exchange of goods but also of

labor. Consequently, manufacturing in our land has declined significantly and with it the influence of labor organizations. The resulting anomie of previously viable working -class families has led to disillusionment about the future and the susceptibility to alt-right views and hyper-nationalism. And to Trump, our high-chair president.

John, thanks for the connections to the economy and an overall social and political picture.

“Simplifying our lives when it comes to material possessions is a good way to start but it marks the start of the journey” is a thought I have been pondering. Thanks for the insight. And by the way,I have cleaned out one drawer!

Flo, thanks for writing and for sharing that you have cleaned out one drawer! I got a good laugh out of that. As the saying goes, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

Dr. Frederick:

I have been pondering the reading for a few weeks. Please allow me to disgorge my thoughts in a somewhat erratically meandering manner.

Aristotle speaks of sufficient internal and external goods necessary for the good life, for human flourishing. Those aren’t one in the same but the same goods are needed. Aristotle says in essence that we cannot be ascetics and find flourishing. Many spiritual disciplines would disagree and state the ascetic life the truer existence, the one closer to God.

The context within which we define the concept of too much is relative and not absolute. Our relative poverty is richness in much of the world. Certain subsets of our culture would find anyone without multiple homes and personal jets impoverished. They would not know how we live such deprived lifestyles. In turn, we do not understand how many in the third world are able to survive much less flourish though many seem to do so. This leads me to apply demographic categories for the defining of sufficient goods.

As one reader pointed out, the United States economy is consumerist in nature. Two-thirds of our $20 trillion in annual GDP is driven by consumer demand for goods and services. We spend to explore new hobbies, gain new understanding, and to buy plastic trinkets worth only pennies of what we pay. Our stuff defines us, allows us entertainment and enrichment, and helps others define us within the context of our capitalist society.

Nearly all reasonable people will agree, and certainly all those in authoritative positions, that living the ethical and just life is laudable. All fallacious appeals aside, there are a minority among society that would say the “good” life as described in your writing was ill-conceived. It also seems an equal number, made up of different members, would agree that having the best stuff is a meaningful goal: to enjoy the best available while on our ride around the sun is not so bad a choice and does not necessarily equate to an unethical life.

We all suffer from bias, and we catch ourselves in judgments based on how someone acts, dresses, what they drive and where they live. Indeed, to have fine things is considered a “success” while to have few or ragged things is often pitied. We feel sorry for their misfortune— missed fortune.

We know stuff isn’t the highest and best attainment in life, but I’m afraid to denigrate stuff and our pursuit of it might be a little convenient right before we look to get that cool new shirt, or dress or pair of shoes.

Truly a difficult subject and a great topic for extended conversation. Thank you so much for your posts that cause us to apply philosophy for living today. And thank you for letting me wander around in my response.

Your student,

Ercel

Ercel,

Thank you for taking the time to write your observant and on-target thoughts. I totally agree that the “right” attitude toward stuff is a vexing question. Having the conversation helps, I think. Thanks for entering into the dialogue with your good insights.