“You can kiss your family and friends good-bye and put miles between you, but at the same time you carry them with you in your heart, your mind, your stomach, because you do not just live in a world but a world lives in you.”

-Frederick Buechner, Telling Secrets

By Norris Frederick

Ninety years old, he’s on the ground, in the garden behind the Wesley Nursing Center. A nurse sees him: “He’s fallen!” She and two staff members rush out, hoping he has not broken any bones. As they near him, my great-uncle looks up at them from where he is kneeling forward, smiles and says, “Aren’t ants fascinating? I’ve been studying their habits here for several days now.” Then he slowly gets up, brushes off the black dress pants he always wears, makes sure he has no dirt on his white dress shirt, and says to them, “Shall we go back inside now?” With the grace of the tennis player that he was for many years, he walks back to the building, doing his trademark whistling.

We knew my great-uncle simply as “Uncle Sneed” or “Sneedie,” short for Nicolas Snethen Ogburn, Jr., and he was as unusual as his name. My grandmother’s brother, he gave me a vision of a life devoted to truth, not to majority opinion.

At age 28, after he graduated from Trinity College and Vanderbilt University, he was ordained as a Methodist minister in 1911. Instead of seeking to lead a comfortable life in a comfortable church, he sailed to Japan in 1912, where he served the church as a missionary teacher until 1941, returning home only at seven-year intervals.

Sneed spent his first few years in Japan learning to read, write, and speak Japanese, then several years serving as an itinerant missionary and preacher on the island of Shikoku. In 1920 he married Maude Hoyle, to whom he’d been engaged for seven years. That same year, he became a professor of English and Religion at a new Methodist University, Kwansei Gakuin, in the city of Kobe. Their son Lanier was born in 1922 and grew up in Japan.

Lanier writes, “With war imminent in 1940, his son and wife returned to North Carolina, while he remained to complete his teaching assignment…. Finally, and with great difficulty obtaining passage, because every foreigner was desperately trying to leave, he was able to buy a ticket (on a Japanese ship!) and docked in Seattle 14 days before the attack on Pearl Harbor.”[1]

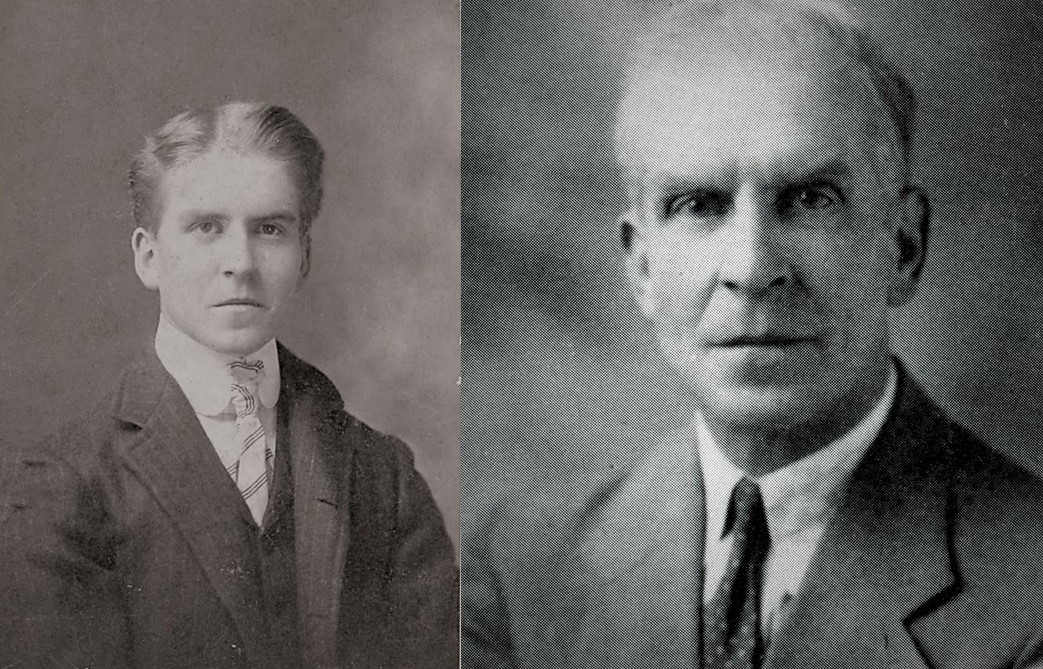

When I look at the pictures above of Sneed above in at age 18, in 1902, and then at age 72, in 1956, I wonder what it felt like for him to leave his home to sail for Japan, knowing he would be there for seven years, with no trans-Pacific phone lines, the only contact through letters. Did his devotion to his religion and his sense of calling deliver him smoothly through those years? Did he suffer terrible homesickness, especially during those first seven years before he married? Did he regret his choice?

Who he was in 1912 formed the basis for his decision to live in Japan, and his life for 25 years in Japan shaped who he was to become.

Who Am I?

I pondered the question “Who am I?” in a previous essay, (click here to read). Since that time, I’ve continued to ponder that question.

One answer to the question of “Who am I?” focuses on self-identify: “what makes me the same person from one time to the next,” ultimately over many years? One perennial answer is that it’s memory that accounts for this continued existence. To update a thought experiment that John Locke offered in the 1600’s, suppose you woke up one morning remembering what you’d done the previous day, remembered a dream during the night about the time you and your brother and parents went to Wrightsville Beach, got up and went to the bathroom, and then looked in the mirror and found you had a new face, a different body?

Assuming you didn’t immediately faint, hit your head and die, you would think that something really, really strange had happened! But that really strange thing happened to YOU, the one who has all the same memories as the day before! (Perhaps you would come to console yourself with the thought that at least you were not like Kafka’s character who was transformed into a cockroach).

To digress a bit, memory is a fascinating thing. Only when I began writing this essay did I remember that my great-uncle Sneed gave me my first tennis racquet when I was about 11. It was old, made of a yellowish wood, with a worn black grip. A wooden press had kept the racquet from warping, but the strings were so old they were brittle. Still, I loved the feeling and the “ping” sound of racquet hitting ball. I’ve never stopped playing, even today, now that I am retired, older than my father when he died. How startling to realize now that my tennis playing started with a gift from my great-uncle.

Or … did I not really remember his gift of the tennis racquet, but unconsciously invent it, trying to fill in some gap of memory? Am I remembering accurately, or am I creating a self-identity that fits a narrative I’ve formed?

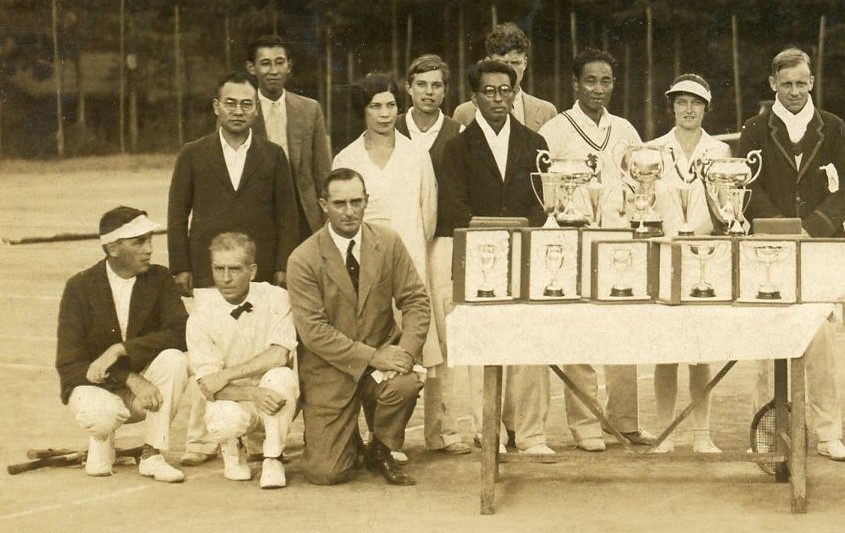

Kobe, Japan, 1932 tournament: Sneed is second from left on the bottom row.

Uncle Sneed and Me

One answer to a question related to “Who am I?” (“Why am I the way I am?”) is that we become the person we are partly through imitating – often unconsciously — the lives of those who are significant to us. As Frederick Buechner writes, “you do not just live in a world, but a world lives in you.”

(For a more complete answer to “Why am I the way I am?” we’d need to consider much more, including the influence of genetics and our choices.)

As a young person I experienced many examples of good traits and some bad ones among my family. Sneed was one who stood out is so many good ways, but also in ones that were puzzling, that went beyond my understanding of “good” and “bad.”

Sneed was a small man, about 5’6” and 140 pounds, but physically fit and emotionally strong. He lived life joyfully and fully. He wrote poetry, loved puns, and sang hymns. Uncle Sneed loved much about Japan, its culture, and its people. In 1931, he published a small book called Little Roads to Understanding: A Venture in International Friendship. He intended it both to help Japanese understand American ways and to help Americans learn how to be friends with people of other nations, hoping that friendship would “ever grow stronger until it finds itself swallowed up in that bigger and ever-growing thing — World Brotherhood!”

Back in the 1930’s, someone who knew Sneed might have said, “Ah, World Brotherhood! There’s the problem, you see, he is so impractical! I mean, Christianity is a fine thing, don’t get me wrong, but you’ve got to use common sense, don’t you? Otherwise, we’ll have people doing things like saying the coloreds are our equals! Common sense, man!”

I admired his hopefulness and that he was not limited by what society deemed common sense, even though I found what he did a little…strange. When he was in his 80’s, you could still see this short man, totally bald except for a few wisps of hair on top, wearing a dark dress suit, walking several miles from his house on Worthington Avenue to the city jail downtown, carrying in a blue and white Japanese scarf the Christian tracts he planned to give to prisoners, hoping to help get them live right. Back then, I thought taking tracts to prisoners was odd, and I doubted how much it would help anyone. But Christianity was central to his life, and he lived a life devoted to his understanding of God, love, and acting rightly.

Today I think people can have a good life with all sorts of religions and worldviews, not just Christianity. I believe that his act of reaching out to those prisoners, making a human connection, was a selfless act – he would not have preached hellfire and damnation to those men, but talked and listened — that inspired some of the prisoners he reached out to. And some of them were drawn to a better life as they were drawn to the love shown by Jesus of Nazareth as embodied in this odd little man.

Once, seeking to help our family, he came to our rather decrepit house to repaint our metal porch chairs a bright green. He brought the chairs to the backyard where we were playing wiffle ball. We twelve-year-old’s never paused our game, let alone offered to help him move the chairs. So, he took a chair behind the protection of a large oak in “left field” of our yard, and he painted the chair there. He was a humble man, and I cringe at the memory of our thoughtlessness.

I thought him strange and impractical, and yet now as I think about it, maybe I have been a bit strange and impractical too. I grew up in the segregated South, with the blatant racism of the times, and the friends I played ball with casually used the N-word. Yet during the years of social division over civil rights — encouraged by the willingness of my Uncle Sneed to be different — when I was 17 I attended a summer-long night class at the black university in Charlotte (Johnson C. Smith), led by a black college student from Chicago. We read Ralph Ellison, The Invisible Man, and James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, among others. Those books and discussions rocked my world and awakened my mind.

When I was 21, I withdrew from my college ROTC program and filed as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. In my early 30s, I became deeply involved in the national movement to halt the nuclear weapons race between the superpowers. I wrote frequent opinion essays about the arms race and its costs for The Charlotte Observer, leading some think I was a bit strange, and therefore not to be trusted, such as a vaguely threatening neighbor who addressed me as “comrade.”

There was such a solidity to Uncle Sneed’s life. That solidity contrasted sharply with the unpredictable life of my family. Our family “secret” was that my father was an alcoholic, of the Jekyll and Hyde variety. Sober, as he was sometimes for weeks and months, he was a kind, quiet, and witty man who we loved deeply. We always wondered how long that would last; we were always on edge. And then one night he would not come home for dinner, and someone would say, “Oh, I’m sure he just had to work late,” but in the pit of my stomach the fear said he would come home late, slamming the front door, cursing at my mother as we children tried to become invisible. Then he would sleep all day, and then he would have lost another job, and we would be on the edge of poverty again. When my high school girlfriend and I were married, my father was hospitalized with another nervous breakdown and could not attend the wedding.

Buechner is right that “you do not just live in a world, but a world lives in you,” but that world in you can haunt you.

Sneed officiated at the wedding of my grandmother (his sister) and grandfather, in 1910. And he co-officiated at my wedding, 58 years after my grandparents’ wedding. I remember thinking during the wedding about how small Sneed looked at age 83. I was so glad he was there.

In the early 1970s, Sneed and Maude moved to The Methodist Home, living first in a cottage on the grounds, and then, as Maude became ill, they moved into the Wesley Nursing Center. I visited him regularly until he died at age 99. Even in his last years when he became senile, he still whistled much of the time, and he seemed at peace.

I have not lived up to his standards in so many ways. At times I’ve been all too practical, following a conventional path when I should have done otherwise. At other times I’ve selfishly done what I wanted to do, rather than what I should have done. I drink. I curse, even if I do try to save those words for worthy occasions. I watch today’s movies, whose display of nudity and sex would horrify him. He could not have countenanced any of those things. I do hope that I’m a better person than I would have been had I not known my great-uncle Sneed. I am grateful for him.

Did I really remember that?

Sitting on my desk, as it has for over 30 years, is a 2 ¼ inch bronze, surprisingly heavy, replica of The Great Buddha of Kamakura, Japan. The original — also bronze — was constructed circa 1252; it is huge: 44 feet tall and weighing 103 tons. Sneed no doubt brought the replica from Japan to his sister, my grandmother. It has an inscription on the bottom. One day when a Japanese student was in my office at the Queens University of Charlotte, I asked her to look at the inscription, and she said, “Oh, this is the big Buddha of Kamakura!” Before that, all those years, I’d never known.

Like Sneed, I’ve been a tennis player, a writer, and a professor, in my case a professor of philosophy. My training in philosophy leads me to ask many questions, sometimes too many for my own comfort, but it’s hard to stop. When I think about the “memory” answer to the question of personal identity, the problems of that theory come to mind: our memories often are incorrect even about recent events, let alone ones of long ago. Just discuss your memories of an event long ago with a friend or sibling, and you will know what I mean. It sometimes seems we are constructing who we are rather than remembering and discovering who we are. We are in part unintentionally “making stuff up” about our life; not all of it, but some of it.

This train of thought leads me to think about whether that memory of Sneed giving me a tennis racquet when I was about 11. Is it accurate, or a false memory subliminally suggested by the first paragraph I wrote about him? Plenty of my other memories don’t agree with those of my siblings and friends, so why not this one?

Recently I’ve been going through family letters. Last week a letter from my mother to her mother – Sneed’s sister – caught my eye. Dated August 25, 1959, the letter so well captures my mother: it is well-written, newsy, funny, and loving. She begins, “Dear Mother, I haven’t not written because I don’t miss you but because I stay in such a stew all the time. Everyone’s gone off tonight, & ‘Peace, it’s wonderful!’”

Then she writes this: “Sneedie met the boys at Independence Park this evening and gave tennis pointers.”

I am astounded as I read this. While just reading, not looking for anything in particular, I discover some verification of my memory of Sneed and tennis! The postmark of the letter tells me I am 11, as I’d remembered, and here he is teaching tennis to my brother Charlie and me.

That letter is such a gift.

Signs, Roads, and Lives

Toward the end of the introduction to Little Roads to Understanding, in which Sneed will offer many suggestions about treating people of other cultures well, he writes, “Sign-boards [traffic signs] can never take the place of roads. One can scarcely keep to the road who keeps his eyes too much toward the boards. Rules for living cannot be a substitute for real living…. Hence, the sooner this little book – only a guidebook – can be discarded, the better……. The catching of the spirit of brotherly kindness which it is endeavoring to breathe, would go far toward rendering its own existence useless.”

Memories of loved ones and their good lives can’t take the place of leading a good life. But their lives can be sign-boards, pointing the way. And more than that, their lives become symbols, themselves sacred, while pointing beyond themselves.

______________________________

[1] The quotation and the facts in the two paragraphs preceding this citation are from a biographical sketch by Sneed Ogburn’s son, Paul Lanier Ogburn, in a book of Sneed’s poems, Whatsoever Things Are Lovely, originally published in 1956, and reprinted in 2003, copyright Paul Lanier Ogburn, Sr., MD.

So glad that you have been delving into the letters we have spoken about and wondered if I ever stumble by your uncle as he walked Worthington Ave to the jail. I would stomp those grounds between shifts at the Red Cross occasionally. While I have some letters from my uncle Sylvester to our grandmother, I never met him as he was a casualty in WWII. Still, those voices speak to us…

Gary, thanks so much for your comments and for sharing that you walked around Worthington Avenue at one point. Yes, as you write, “Those voices speak to us.”

Norris

Norris, this article is so beautiful, sweet and meaningful to me. I have vivid memories of all involved and I remember how incredibly special Sneedy always was. I do actually remember you playing tennis with him or at least Mama telling me that’s where you were. He was to me, like Gannie, a perfect example of a true Christian. I remember one time when I was ‘single again’ and my car out of commission, borrowing his car to go to a wild n crazy party. I look back on that time of my life with gratefulness that I returned it intact the next day and shameful that I borrowed it to go somewhere he would not have approved of. I could go on & on but I’ll leave room for others to comment.

I’ll always remember the Buddha. At one time it was in Gannie’s china cabinet. I seem to remember having it at one time but I don’t recall passing it on to you. See there – there’s that memory of ours playing tricks again.

Virginia, thank you very much for sharing your thoughts and memories, and especially of the time you borrowed Sneedie’s car. That’s a wonderful and honest story. As for your having the bronze Buddha at one time…, I believe it was Plato who first said, “Finders, keepers”! 🙂

Norris

Thank you, Norris, for sharing your story of Uncle Sneedie but also sharing so much of yourself and your life. We share similar experiences from our past and this brings back many memories of them. The transformation you explain at age 17 was about the same time you told me to read, “Black Like Me”, which changed me from the bigot I was to a more enlightened person. Now 57 years later, I am still seeking enlightenment. Thanks for helping me along the way.

Ike, thank you so much for your comments and for the connection, when we were about 17, to “Black Like Me.” That gives me another memory to think about. many thanks, Norris

Another masterpiece of writing means much to me from my friend, Norris. Each time he shares I learn new ways of thinking of my history, his history, and the early years in the late 1960s when we were college students/friends together.

I am reminded of the most important mentor and male influence is my life, Edward R Zane Sr, born in late 1890s, who also was short in height and taller in influence than anyone I have ever known. He was age 69 when I was 22 and had recently finished my years at Davidson College. He fought in WWII, came back home to Washington DC in 1918, slept on a park bench in Washington DC, and put himself through college and law school. He was the financial genius in the building of Burlington Industries from a single mill to become the largest textile company ever. Like Uncle Sneedie, Mr Zane grasped the reality of discrimination against minorities, and went into the African American communities and A&T University in particular in Greensboro NC, when Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated. His ability to hear other people, listen, and build shared values was profound. He also did not suffer fools willingly.

Norris, thank you again for your brilliance and deep sharing of family values and histories.

Charles, thank you so much for your kind comments. And thanks so much for telling us about your main mentor and male influence.

Norris

I never met Sneedy, sadly, but I so appreciate you sharing his story, and a bit of what he has meant to you. I was also struck by the incredible wisdom of his words, “Sign-boards can never take the place of roads. One can scarcely keep to the road who keeps his eyes too much toward the boards. Rules for living cannot be a substitute for real living…”

I will never forget a conversation with a pastor colleague who said, “The Bible is a rule book, not a relationship book.” I remember thinking at the time what I still think today – if the Bible is just a rule book, then we’ve missed the point of it. God did not create us to simply follow a bunch of rules. God created us to LIVE. Fully. Abundantly. Eternally.

Scott, thanks so much for your comments and for your insights in connecting Sneed’s “Rules for living cannot be a substitute for real living” to your point that “if the Bible is just a rule book, then we’ve missed the point of it.”

As we get older the pursuit of truth means different things. The letter of your Mom is the very center of this memoir. Our memory moves towards things that are now meaningful. We reconstruct a story from a new point of view. I love how your memoir moves across time back ant forth. The story is how we create new meaning in our lives right now. Your essay is a beautiful example of how to do it. I love how you pin down your age and your Mom’s letter comes complete with a factual story which wonder of wonder fits with your memory of the gift. Now can you place yourself on the court with your uncle at the net spooning soft shots to your forehand? Of course, because you have done it yourself for your son or someone else. And why could you do it? Maybe because of Uncle Sneed.

Jack

Jack, thank you so much for your insightful analysis of my post about Uncle Sneed. You make excellent points about the post that I was not fully aware of! I love your final comments that begin with “Now can you place yourself at the net…” I can tell this comment is written by a tennis player and a philosopher. 🙂